Power never takes a back step - only in the face of more power.

- Malcolm X

It was the winter of 2013, and I was watching the second episode of the BBC documentary Simon Schama’s Shakespeare. The introduction had arrested my attention:

The question of who kings and queens truly are obsessed the greatest dramatist of all time. In many of Shakespeare’s greatest plays kings and queens stalk across the stage: grandiose, bloody-minded, demented, sociopathic. And the question Shakespeare asks of them more insistently, more deeply, more tragically than anyone before or since is this: what happens when a human puts on the crown? Can they be just like us and not at all like us? What happens when the human animal breaks through the mask of royalty.

Shakespeare’s plays were performed right in front of Elizabeth I and her successor James. There they sat in their finery watching stage versions of themselves murder their way to the throne, go mad, and get turned into pitiful creatures. Shakespeare must have thrived on the thrill of it. Having his actor-kings say the unsayable in front of real-life monarchs. He probed deeper into the royal mind than anyone before or since; exploring the great themes of power, war, and death. From that exploration of kingship, Shakespeare revealed the darkest truths, not just about them, but about us too.

Thus drawn into this exploration of kingship, I watched as Elizabeth I’s reign during the defeat of the Spanish Armada was compared to Shakespeare’s Henry V, and the queen herself to its eponymous protagonist. The program then turned to the events of an attempted coup d’état, known as the Essex Rebellion, wherein the Earl of Essex and his supporters attempted to turn Elizabeth into a puppet queen and install Essex as the puppetmaster. The night before the failed coup, the conspirators had paid for a private showing of Shakespeare’s Richard II, which dramatizes the deposition of the titular king. After explaining that the rebellion had failed and the ringleaders were executed, Schama mused, ‘Shakespeare lived in an age when writing was a dangerous game. Christopher Marlowe was murdered. Thomas Kyd was tortured. Ben Jonson was thrown into jail. So what about Shakespeare? After the Essex Rebellion, could the writer of Richard II be had up as an accessory to high treason?’ Good question.

The answer given by Michael Boyd, Artistic Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, was:

It was a dangerous dance, there’s no doubt about it, and you had to become as good with antithesis and metaphor as Shakespeare did, to ski along that razor blade. The reason that Shakespeare managed to stay out of jail and got his plays onstage and the reason Shakespeare escaped the lesser role of essayist and commentator on the times and achieved the role of the greatest dramatist ever was that he dramatized opposing positions in a way that it is almost impossible to nail him down.

WTF?

In my experience, and with apologies to Mr. Boyd, power doesn’t take a back step in the face of literary antithesis and metaphor, regardless of its brilliance. After all, the long and sordid history of state control of art and artists can hardly be described as illustrative of a fair-minded sensitivity to fine distinctions, can it? Not even at the best of times. But this was not the best of times. It was, as we had just been reminded, ‘an age when writing was a dangerous game’. And the play had been performed just before an attempted rebellion, for the rebels! It simply didn’t make sense.

My point here is not to pick on Schama and his guest. It is puzzling that Shakespeare escaped from the clutches of Elizabeth’s henchmen scot-free when so many of his contemporaries did not. What’s more, it generally took far less than a connection to an attempted rebellion to provoke the ire of the Tudor state. Shakespeare’s impunity cries out for an explanation. Given the mainstream prohibition on questioning that Shakespeare was undoubtedly a commoner from the small Warwickshire town of Stratford-upon-Avon, Boyd’s explanation is just as good as any, I suppose. I do not abide prohibitions on my thought, however.

The whole question reminded me of a theory I’d encountered, that ‘Shakespeare’ was actually a pseudonym used by someone else, usually believed by the theory’s proponents to be a nobleman. I’d seen the Frontline documentary Much Ado About Something a number of years before, which laid out the problems with the orthodox story regarding ‘William Shakespeare’. Although I’d been struck at the time by how surprisingly unsatisfactory was the answer given by the defenders of the orthodox story, I’d not really followed up on the question further. The so-called Shakespeare Authorship Question certainly hadn’t been front of mind when I’d sat down to watch ‘Hollow Crowns’ that evening. But it was now front and center as I watched the program deal with the remaining few years of Elizabeth’s life and then begin to describe the opening events of the reign of her successor, James VI and I.

The narrator proceeded to describe what is believed to have been the first performance of a Shakespeare play for James, at Hampton Court, during the 1603 Christmas season. Schama explained, ‘[We] don’t know exactly what plays were performed that Christmas but it seems very likely that for the King and his Danish queen, it would have been the Danish play - Hamlet. Where else had they spent their honeymoon but Elsinore Castle?’

Reviewing certain plot points of Hamlet, Schama declared:

James would have loved the melodrama, but as Hamlet unfolded he must have felt increasingly ill at ease because what James was watching was a reflection of his own life played out on stage. His father, Darnley, had been murdered. The murderer, Bothwell, had married James’s mother, Mary, Queen of Scots. They lived as King and Queen, flaunting their crime like Claudius and Gertrude. This nightmare haunted James and here it was again played out right in from of him.

This was the final straw. What sort of suicidal maniac would present an early seventeenth-century king with a play that would make the monarch ‘ill at ease'? Surely only a madman would, ‘in an age when writing was a dangerous game’, re-enact the life events that constituted the ‘nightmare’ that haunted the one man with the absolute power to order his torture and killing. What’s more, he got away with it. Again.

I tried to make sense of all this and watch the show at the same time. Eventually, I managed to come to the following thought: ‘Hmm. Maybe Shakespeare was actually James himself…’.

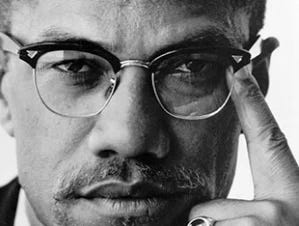

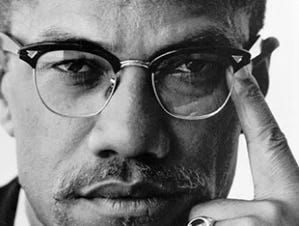

I was able to watch the remainder of the program in peace, having decided to check it out afterwards. Later that night, I searched the Internet for answers and discovered that I was not the first person to suspect James’s involvement. I found out that none other than Malcolm X had proposed it in his autobiography, published posthumously in 1965, a number of months after his assassination. I was able, with ease, to find online the few paragraphs he devoted to the idea. I then searched, in vain, for any well-reasoned arguments against the candidature, finding only a handful of comments - these being of the quality typical of comments that one tends to find online. To my great surprise, the Internet had been unable to provide me with a satisfactory answer to my question.

I widened my search to the holdings of the library at the University of British Columbia, trying to find evidence that would tend to disprove this theory that James was the true author of the works of Shakespeare, focussing at first on the facts surrounding James and his life. I naturally assumed, initially, that I would fairly quickly find some good reasons why this ridiculous notion wasn’t true, and that I would be able to move on with the rest of my life. This was not to be.

The truth is, I knew astonishingly little about the man. I don’t particularly blame myself for this lack of knowledge. King James, despite his rank as the fourth-longest reigning monarch in British history,1 is virtually invisible to our modern culture. This relative invisibility persists despite the fact that his immediate predecessor in Scotland - his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots - is a well-known figure, and his immediate predecessor in England, Elizabeth I, is nothing less than a historical superstar. One of the strange things about this invisibility is that his life, it seems to me, is at least as fascinating as the lives of his mother and his cousin Elizabeth.

The cultural association with Shakespeare is a particularly good example of this strange phenomenon. Unquestionably, Shakespeare is associated in our culture with Elizabeth to an astronomically greater extent than with James, despite that so many of the plays that are overwhelmingly regarded as among his greatest (e.g. Othello, King Lear, Macbeth) date from James’s reign.2

The more I looked into the life of James, the more unlikely it seemed that I would disprove my theory. Indeed, the more I compared James’s life to the works of Shakespeare, and vice versa, the more the evidence seemed to suggest that the two subjects were inextricably linked.

Including both his reign in Scotland and his reign over England and Scotland.

Although, amazingly enough, Hamlet does not - it was unequivocally written before James became King of England. This fact was not mentioned in ‘Hollow Crowns’, and I was unaware of it until I began my research.